Lionfish: Risky but Rewarding

courtesy to : www.fishchannel.com By Scott W. Michael

Lionfish are beautiful, but stay away from their sting.

Certain fish could be considered icons of the marine aquarium hobby. A short list of saltwater "celebrities" would vary at least a little among experienced aquarists, but one species that would no doubt be near the top of this list is the volitans or common lionfish. When I worked at a retail fish store, I sold many of these fish and encountered many people who set up saltwater tanks because they fell in love with this ornate creature.

The volitans lionfish is not the only amazing member of the subfamily Pteroinae, a group of fish known collectively as lionfish (or less often as turkeyfish, firefish or butterfly cod). There are a number of lionfish species that enter the aquarium trade. Although most are considered to be relatively durable aquarium fish, some are more demanding than others, and all require some special care if they are going to thrive in captivity.

In this article, I'll use a question and answer format to share information on this remarkable group of fish. These are questions that hobbyists have asked me over the years.

How many species of lionfish are there?

Lionfish are members of the family Scorpaenidae (scorpionfish) and the subfamily Pteroinae. There are six genera in this subfamily, and approximately 22 species. See "Lionfish Species" to the right for a list of the species in this subfamily. The fish you most often see in the aquarium trade belong to two genera: Dendrochirus and Pterois.

There is some debate as to the validity of some of the species in the genus Pterois. This is especially true for members of the volitans species complex. There are a number of species in this group that are very similar, including the Kodipungi, Japanese, Indian, Russell's, longspine and, of course, volitans lionfishes.

These species are thought to differ in one or more of the following characteristics: dorsal spine length, markings on the median fins and number of fin spines. It is thought that P. volitans is found in the Pacific Ocean, whereas the Indian Ocean form is actually a distinct species known as P. muricata.

How do the two species differ? The Indian lionfish has one less ray in the dorsal and anal fins, and the pectoral fin rays are slightly shorter than those of P. volitans. Do not confuse P. muricata with P. miles (a name formerly used for the Indian Ocean form of P. volitans). Pterois miles is a separate, rare species apparently limited to murky coastal habitats in the northern Indian Ocean. These are subtle differences that most aquarists will not notice.

How venomous are lionfish?

As mentioned, the lionfish are members of the scorpionfish family. These fish get their name from their venomous dorsal, pelvic and anal fin spines. These spines are like hypodermic needles; each spine is connected to a venom sac situated in the dorsal musculature of the fish. When these spines penetrate the flesh of another fish or human, venom is injected through a groove in the spine.

On a recent trip to the Philippines, I made the mistake of placing my finger on the dorsal fin of a shortfin lionfish (D. brachypterus). The resulting envenomation was similar to a bee sting, and the pain was relatively short lived. That said, I know someone who was stung on the thigh by a large volitans lionfish and ended up on the deck of the boat writhing in pain. In this case, the pain lasted for hours. Zoologist H. Steinitz was stung on the finger by a 4-inch P. volitans. Regarding this sting, he said, "I was tortured by pains beyond measure, and yet the pain was still growing more intense. It is just short of driving oneself completely mad."

The most common symptoms associated with lionfish stings are intense pain in the affected area and swelling. The pain subsides as treatment is administered, and in most cases subsides within 24 hours. More serious envenomation may include weakness, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, delirium, fever, chest and abdominal pain, and even unconsciousness.

The severity of an envenomation event may depend on the species and the size of the lionfish. I have not been able to find any information indicating if toxicity of the venom of various species differs, but as in venomous snakes and scorpions, this could be the case. It would also make sense that a larger lionfish may inject a large quantity of venom. In very rare cases, lionfish stings have caused death.

Therefore, make sure you treat your lionfish with the utmost respect!

What do I do if I get stung by my lionfish?

If you are stung by your lionfish, immediately immerse the wound in hot, nonscalding water (from 110 to 113 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 or 40 minutes or until pain has diminished), or heat it with a hair dryer. The heat will denature the protein that constitutes the venom and prevent it from spreading through your body. If the aforementioned symptoms occur, it is advisable to seek medical attention immediately.

How are most aquarists stung by lionfish?

Although there are fanciful stories in the old aquarium literature of lionfish dashing across the tank to stab their human keepers, the venomous dorsal spines of lionfish are used primarily for defensive purposes. There are situations in which at least certain species of lionfish employ their spines in an offensive manner. When fighting for females, male lionfish (especially Dendrochirus spp.) regularly spar using their dorsal spines to inflict damage to their rivals. Although it is unlikely your lionfish will "attack" you, they will raise and direct their spines toward a potential threat, and this could include a hand moving in the aquarium.

In most cases of lionfish stings, aquarists are stung while cleaning the tank or transferring a lionfish from one tank to another. The preoccupied aquarist accidentally bumps or brushes into the lionfish's needle-sharp dorsal spines. In order to prevent envenomation, be vigilant when working in a lionfish's aquarium.

Many lionfish hide behind pieces of aquarium décor and can easily go unnoticed. Locate these fish before cleaning the tank to prevent accidental contact. Also, you should never place your hand or arm too near a lionfish's dorsal spines, because if they perceive you as a threat, they can arch their backs and thrust their dorsal armament forward to jab you.

What and when do lionfish eat in the wild?

The diets of lionfish vary among genera and species. Studies have shown that members of the genusDendrochirus feed mainly on crustaceans, while Pterois species (especially the larger, more active members of the genus) include more fish in their diet. For example, adult volitans lionfish feed more heavily on fish than most other members of the genus, but crabs and shrimp (including the banded coral shrimp, Stenopus hispidus) are also important in their diet. With larger Pterois, studies suggest that crustaceans are also more important in the diets of juveniles than adults.

Most lionfish feed at dusk or in the dark. For example, the spotfin lionfish emerges from its daytime hiding place (usually a crevice or a cave), and begins to hunt shrimp and crabs in the late afternoon. It continues these hunting forays into the night. The volitans lionfish and some of its close relatives are more likely to feed during the day than their more secretive relatives. For example, in Japan, I often saw large Japanese lionfish strike at cardinalfish that moved too far from cover in the early mornings.

Some lionfish may engage in cooperative hunting; individuals will work together to increase their chances of hunting success. Groups of volitans lionfish will herd schools of small baitfish up against the reef, isolate a smaller group, then launch their attacks. In Papua, New Guinea, I observed a fascinating example of P. volitans'cooperative hunting behavior in Milne Bay. It occurred on a barren sand slope, where there were solitary and clustered venomous sea urchins (Astropyga radiata). These urchins were with the commensal urchin cardinalfishSiphamia versicolor. At dusk, I observed three large volitans lionfish surrounding a solitary urchin. The cardinalfish would retreat from one side of the urchin to the other to get out of the path of the nearest lionfish - but when it did, it would swim into the strike zone of one of the other waiting predators.

Although it can be interesting to observe lionfish consuming feeder fish, feeder fish do not provide a nutritionally complete diet. It may be necessary to feed your lionfish live food initially, such as live ghost shrimp, fiddler crabs, freshwater crawfish, feeder guppies, mollies, or even cardinalfish or damselfish. Unfortunately, many aquarists feed their lionfish live feeder goldfish.

This is probably the worst possible choice. Raw goldfish flesh contains thiaminase, an enzyme that causes the breakdown of thiamin. If you feed your lionfish a diet that consists only of goldfish, they may become thiamin deficient. This can result in feeding cessation, clamped fins and problems with the nervous system. Yes, I have seen lionfish kept a number of years and fed only live feeder fish, but you are more likely to have success if you do not feed your lionfish live feeder goldfish. I prefer feeding live ghost shrimp to newly acquired lionfish. Before you introduce the shrimp to the lionfish tank, feed these crustaceans a nutritious frozen prepared food. Then, feed the shrimps to your lionfish. This is known as "gut packing"; you are packing the guts of the shrimp with nutrients that will be passed on to the predator consuming the shrimp.

Although some species are reluctant to accept anything but live food, you should attempt to switch your lionfish to nonliving food. One of the easiest ways to do this is to take a piece of marine fish flesh or a piece of fresh shrimp, and make it "swim" around the tank by attaching it to the end of a piece of rigid air line tubing. There are other ways to dupe your lionfish into taking onliving food - just use your imagination.

How often should I feed my lionfish?

In the wild, a lionfish will consume from one to more than 10 small- to medium-size prey items per day. In the aquarium, it is preferable to feed your lionfish two or three times a week, depending on the temperature of the aquarium (at lower water temperatures, you will not need to feed them as much). If you feed a captive lionfish too much or do not vary the diet, fatty degeneration of the liver may occur. This condition can cause liver failure, which leads to suppression of the immune system, hemorrhaging and anemia.

It is thus important to vary the diet and not to feed your lionfish too much. It is also important not to feed your lionfish large prey items. These fish have been known to kill themselves by overeating. You should feed larger amounts of small prey items rather than one large morsel.

Which lionfish are most difficult to keep?

In my opinion, the most demanding species is the twinspot or Fu Manchu lionfish (Dendrochirus biocellatus). This species is very secretive and can be difficult to feed, especially if kept in a larger aquarium and/or housed with aggressive food competitors. I prefer to keep this species on its own in a smaller tank (20 or 30 gallons). You will need to feed it live ghost shrimp to initiate feeding and may have to continue feeding it live food because it is more difficult to switch to nonliving foods. In general, members of the genus Dendrochirus require a little more attention, especially when it comes to feeding, than Pterois.

What kinds of fish can be kept with them?

Keep lionfish with fish tankmates too large to eat. Lionfish swallow their prey whole, so as long as a fish is too large to swallow, it will typically be ignored by lionfish. That said, know that some lionfish can eat relatively large prey. This is especially true of fish that are longer in body shape, such as certain wrasses and gobies.

Deep-bodied fish, such as angelfish and butterflyfish, are less attractive targets. Although lionfish rarely sting fish tankmates, this can occur. This is more likely to happen with less agile tankmates, like other scorpionfish, puffers and porcupinefish. These fish have been known to accidentally land on or ram into lionfish spines.

While their venomous spines are effective for dissuading some predators, lionfish still have their enemies. I have had frogfish eat lionfish that were as long as they were, and there are reports of sharks, coronetfish and groupers eating lionfish. I have also seen larger angelfish, triggers and puffers nip at lionfish fin spines. Just because lionfish have a potent defense system does not mean they are invincible to attacks by other fish.

Can I keep more than one lionfish in the same tank?

Some lionfish will behave aggressively toward members of their own kind. For example, twinspot and shortfin lionfish have been known to chase one another - incessantly, in some cases. The submissive fish (the one being chased) will often stop feeding and may perish if not removed from the aquarium. Many Pterois tend to be more tolerant of their own species, as well as other lionfish species.

When placing more than one lionfish in the same tank, it is best to add smaller individuals first. Of course, problematic aggression is also less likely if the tank is larger. When keeping lionfish together, make sure you spend time watching them. If an individual is harassing others, you will need to remove the aggressor or those individuals getting picked on to ensure their survival.

Aggressive encounters between lionfish are typically limited to lateral displays, gill cover flaring and head shaking. If one individual does not back down, the combatants may bite each other. For example, an aggressive shortfin lionfish may grasp the head of an opponent in its mouth and vigorously shake it from side to side. This behavior can result in damage to the jaws of the fish that is attacked. Individuals may also bite the flanks of a species member. Some lionfish will ram each other with their venomous dorsal spines.

Although a lionfish stung by a species member will usually not die as a result, it can cause temporary distress, including an increased respiration rate (as much as three times its normal rate) and decreased swimming activity. I have also seen Dendrochirus lions in the wild that were missing eyes, which I would guess was the result of spines poking into them.

Can lionfish be kept in a reef aquarium?

Yes! Lionfish can make attractive and interesting additions to a reef aquarium. They will not harm sessile invertebrates, such as sponges and corals, but they are a threat to ornamental crustaceans.

So, if you decide you can live without a cleaner shrimp or anemone crab, a lionfish is an ideal addition to a reef tank. You can keep larger hermit crabs (too big for your lionfish to swallow) with lionfish, but they may eat small hermits. Of course, a lionfish is likely to ingest any fish that can fit in its mouth.

Although lionfish are not for everyone, they can be attractive and very interesting inhabitants in a fish-only or reef aquarium. Be sure you are aware of the risks involved as a lionfish owner (especially if you have small children at home), and be prepared to spend some time ensuring they get enough of the right foods. If you have other questions about lionfish, make sure you send them to Aquarium Fish Intl.'s "Saltwater Q&A." Until next time, happy fishwatching!

Lionfish :

Twenty years of research experience has brought Scott Michael sponsorship and funding for projects as varied as the study of the draughtsboard shark in New Zealand, hammerheads in the Gulf of California, in addition to creatures as varied as frogfishes, green sunfish, and stingrays. He has worked alongside some of the worlds top marine animal experts, and published several well received scientific papers on his findings.

As a writer he is best known for his definitive work "Reef Fishes; a Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Captive Care, Volume 1." He is also author of more than 60 popular articles for aquarium and dive magazines, was a contributing editor to a leading aquarium publication for two years, and for the past six years has had a regular monthly column in Aquarium Fish Intl.. He was also been co-author of two marine CD ROM programs. He is a major contributor to and partner in perhaps the best known educational marine life and dive travel website www.coralrealm.com. Scott was also a scientific consultant and filming assistant for the Mike DeGruy film, "Sharks: On Their Best Behavior," and also contributed to a Marty Snyderman film, "View From the Cage."

Scott lives with his wife Janine, herself an accomplished underwater photographer and active partner in his research, in their home on Lincoln, Neb. They share their home with their golden retriever, Ruby.

Lionfish Care guide:

Information and tips for successful captive care and home husbandry.

courtesy to : www.lionfishliar.com Greg Hix & Renee Coles-Hix

One person’s Devilfish may be another’s Turkeyfish, and both of those are yet another person’s Lionfish…are you confused? Not to worry, for the purpose of our little discussion, we’ll call them Lionfish. Lionfish are members of the subfamily Pteroinae, which places them within the family Scorpaenidae. Pteroinae includes five genera and about sixteen species, however, this article will focus mainly on the two genera of lionfish typically found in the aquarium hobby, namely Pterois (large and medium bodied lionfish) and Dendrochirus (dwarf lionfish). Of these two genera, nine species are typically available to hobbyists. We will however, also include one member of the genus Parapterois, as this fish does indeed occasionally show up in the hobby.

General Description and Habitat:

Lionfish are typically found in the Indo-Pacific, South Pacific, Red Sea, Sea of Japan, and are generally associated with tropical reefs, where they can be seen living on both hard and soft

substrates, often in caves, crevices or under overhangs by day, and emerging to hunt in the dim light of the evening and pre-dawn hours. It is during these low-light hours that the wild, striped patterns and dermal tassels of the lionfish allow them to blend in with shadows and reef growth, similar to the way tigers and leopards blend into the vegetation on land.

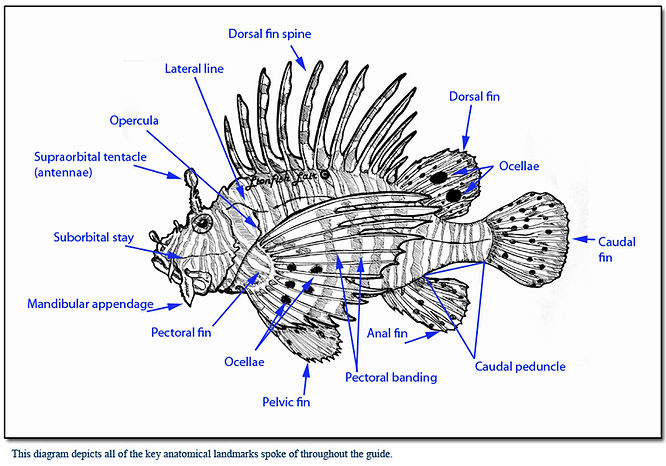

While the identification of certain Scorpaeniforme species can sometimes be tricky, for the most part, lionfish tend to be more clear-cut, especially the dwarf species. All lionfish do share some common morphological traits which include large heads, mouths, and eyes, as well as a bony ridge running from the eye across the cheek (known as the suborbital stay). Long, non-venomous rays are present on the pectoral fins, and of course, there are the stiff, daggerlike dorsal, pelvic, and ventral fin spines which deliver the painful punch of the lionfish’s venom. The toxicity of this venom varies from family to family, with lionfish being the least toxic and stonefish being the most toxic, and in some cases, deadly.

Cuticle Molting:

Although they tend to be more mobile than many of their cousins (scorpionfish, stingfish, and stonefish), most lionfish go through periods of inactivity such as waiting for their evening hunt or sitting around while a meal is digested. During these sedentary periods, various algae, hydroids, bacteria, etc. sometimes decide to settle out of the water column and attach themselves to the lionfish's skin. Fortunately, lions and many other scorpionfish have developed a very thin protective skin, called a cuticle, which they can shed periodically to rid themselves of these encrusting critters. It is also one of the reasons this family of fish are fairly disease resistant. Contrary to what many believe, this is not the fish’s mucous layer, nor is it the fish expelling venom into the water column.

The frequency of this molting varies from species to species, and in some genera such as Rhinopias, it can be as often as weekly. Prior to molting, the fish may become noticeably dull, and may even have a slight cloudiness to their eyes, since the cuticle covers their entire body. You may also see the fish gilling and contorting its face in particular in an effort to loosen the old cuticle. Finally, most fish give a few darts around the tank, and the old cuticle floats away like a diaphanous, milky ghost. Sometimes a fish may go a bit off its feed while preparing to molt, as they usually can’t see as well during this time. We actually have a P. volitans that faces into one of the closed-loop returns and allows the flow to loosen its cuticle. Once your fish molts, it will be very bright and shiny in its new duds. Of course, a sick/infested fish will overshed its cuticle in an effort to stay clear of parasites. If you notice this, you’ll likely need to intervene medically and treat for a protozoan infestation.

Let's Meet Some Lionfish:

Dwarf Lionfish :

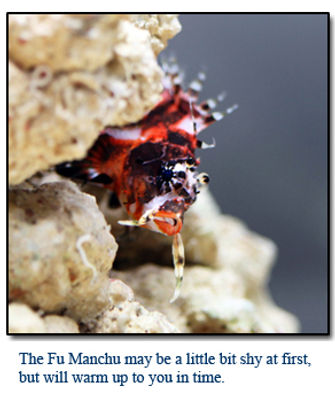

1-Dendrochirus biocellatus

(Fu Manchu Lionfish, Two-spot Lionfish)

Maximum Size: 4.75" TL (~12 cm)

Natural Habitat: Occurs on and around reefs in the Indo-Pacific: Mauritius, Reunion, Maldives and Sri Lanka to the Society Islands, north to southern Japan, south to Scott Reef.

Depth: Approximately 3 to 130 ft (1 to 40 m).

Minimum Tank Size: 30 g (114 l)

This little lionfish is one of the most striking dwarf lions in appearance as well as one of the hardest to keep. The base color of this species is red/orange with dark, almost black mottled stripes and specks on its body with white highlights on its face, mandibular extensions, and fins. These mandibular appengages resemble a mustache, and have given rise to this fish’s most common name Fu Manchu. The second dorsal fin is adorned with two eyespots (ocellae), which give this fish its species name: biocellatus, which means "two eyes". It should be noted however, that some specimens do indeed have a third ocellus on this fin (we jokingly refer to these specimens as triocellatus around our house). Their pectoral fins are smoothly rounded and resemble a Fandango dancer's fans, with only the lower few ray tips forming a serrated edge. All in all, the Fu is a very handsome fish.

You're probably already wondering why the Fu Manchu is considered a bit tough to keep. There are a few reasons: First, these fish tend to be poor shippers, so acquiring a healthy specimen is of utmost importance. Secondly, they are shy, especially at first, and can be rather difficult to wean onto prepared foods. To that end, it is important for this fish to have plenty of rockwork with caves and overhangs to shelter in until it is acclimated to its surroundings. In my experience, the fact that cryptic fish have places to hide will actually make them more adventurous simply because they know that have a safe house handy if needed.

Finally, the Fu is a fairly weak swimmer, preferring to scurry and crutch along the substrate and rockwork. This results in this species being a poor competitor for food when kept with aggressive feeders. This brings us to the subject of feeding your charge. Fu Manchus are about as cautious and deliberate as they come, and this extends to their feeding habits. Their natural food consists of shrimp and other small crustaceans, so saltwater or freshwater ghost shrimp (gutloaded of course) are the first food of choice for your fish. Once you get your fish accustomed to feeding, you can begin the weaning process, which can sometimes take two or three months for a stubborn fish, or it may never happen at all. Once your fish is weaned, it will usually become a typical lionfish and will accept many different foods from a feeding stick or even the water column.

While we’re discussing the feeding habits of D. biocellatus, we would like to mention their fascinating and bizarre hunting behavior. Once a prey item is sighted, the fish will creep up and begin to shake its head from side-to-side while it flares its opercula. Once it is within striking range of its prey, the lionfish will begin to rhythmically twitch its dorsal spines back-and-forth while vibrating the lower tips of its pectoral rays to confuse the food item. Finally, the lion strikes and sucks its hapless prey into its mouth a la Hoover.

While most lionfish exhibit slow, even respirations, it is important to realize that the fu manchu's normal breathing rate always seems to be rather fast, so don't worry if you notice this. One final note regarding the Fu Manchu is that it is probably the most intolerant of conspecifics of any of the lionfish species. Even in larger setups, these fish will seek each other out and fight. It is conjectured that a M-F pair may not fight, however, unlike D. brachypterus, D. biocellatus is not sexually dimorphic/dichromic, thus it is impossible to discern the sex of this species.

2-Dendrochirus barberi

Green Lionfish, Hawaiian Lionfish

Maximum Size: 5”-6” TL (13 - 15 cm).

Natural Habitat:Occurs in association with reefs, drop-offs, and rocky caves. Eastern Central Pacific: Hawaiian Islands. Recently been reported from Johnston Islands

Depth: 1 - 50 m (~ 3 - 164 ft).

Minimum Tank Size: 40 g (~ 151 l).

This species is one of the two lionfish indigenous to the Hawaiian Islands, and is one of our favorite dwarf lions even though it is kind of a sleeper in the hobby, mostly due to their comparatively drab coloration (mostly grays and browns) as adults. Juvenile specimens often have pretty green banding on their pectorals and long supraorbital tentacles (antennae), both of which are lost as the fish reaches adulthood. The caudal, second dorsal and anal fins are adorned with yellow spots, which are one of the telltail visual traits of this species. Additionally, this species sports a pair of mandibular appendages, although they are not as pronounced as those seen on the Fu Manchu. Another feature that sets this little lionfish apart from its cogeners is the glowing solid red coloration of its irises once the fish matures. No other lionfish shares this trait, and it is indeed something to see. The scales of the barberi have a fuzzy appearance, similar to that of D. brachypterus, and this fish is commonly mistaken as a fuzzy dwarf. The photos of our specimen show how its body and eye coloration change as the fish matures.

In terms of habits, this fish is a bit more cryptic than D. brachypterus, however, not terribly so. Like pretty much all lionfish, they do indeed learn to recognize the “food god” and will be there to greet you.

Care for this lionfish is similar to that of the fuzzy dwarf. Like its fuzzy cousin, D. barberi is sexually dimorphic, and can be sexed in the same manner. As mentioned, this delightful little lion isn't super common, and isn't the showiest, but well worth keeping if you can find one.

3-Dendrochirus brachypterus

Fuzzy Dwarf Lionfish, Short-Fin Turkeyfish

Maximum Size: 5”-6” TL (~ 13 - 15 cm)

Natural Habitat:Occurs in association with reefs, drop-offs, and rocky caves. Indo-West Pacific: Red Sea and East Africa to Samoa and Tonga, north to southern Japan, south to Lord Howe Island; Mariana Islands in Micronesia; the Arafura Sea and Australia.

Depth: 1 - 68 m (~ 3 - 223 ft).

Minimum Tank Size: 40 g (~ 151 l).

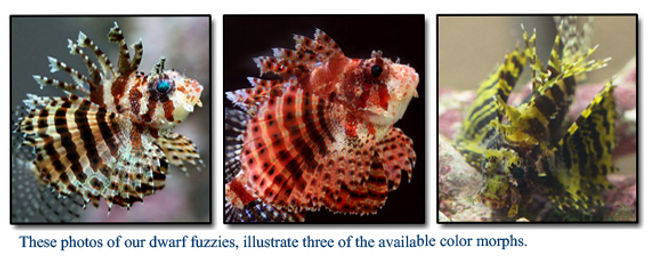

Whenever we're asked to recommend a single dwarf lionfish species, this is our choice, hands down. Fuzzies are pretty, hardy, and personable fish, and have relatively small mouths when compared to many other lionfish species. As their most popular common name implies, the scales of this lionfish have a fuzzy appearance to them. Although these fish come in three basic color morphs (brownish, red, and yellow), they can be virtually any combination of these hues. The brownish morph is the most common, and the yellows are a pretty rare find, as this color morph is only found in fish that hail from the Lembeh Strait and typically command a high price ($300-$400 usd).

The rays of the semicircular pectoral fins are connected by a membrane and are adorned with dark bands and specks. This species is sexually dimorphic, with males exhibiting six or more defined dark bands on their pectorals while females have four to six dark bands. Additionally, adult males have longer pectorals that extend past the caudal peduncle as well as larger/broader heads.

Although a little tight, a properly-aquascaped 30 gallon tank will house a single specimen, M-F-F trios can be kept in larger setups of at least 60 gallons. It is important for multiple fuzzies be properly sexed as males will indeed fight.

Fuzzies are generally out and about once they become accustomed to their setup and will brazenly beg to The Food God when they see someone enter the room. Even so, they should be provided with caves and overhangs to give them that comfort factor. In fact, many fuzzies have their own special attention-getting antics, such as learning to spit water at their keepers (they're surprisingly accurate!).

This little lion makes a great community/reef fish (with proper tankmates of course), and pretty much keep to themselves as long as their tankmates aren't snack-size and show them the same respect.

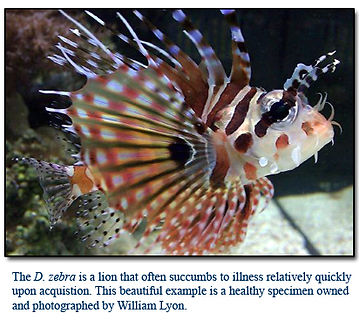

4-Dendrochirus zebra

(Dwarf Lionfish, Dwarf Zebra Lionfish)

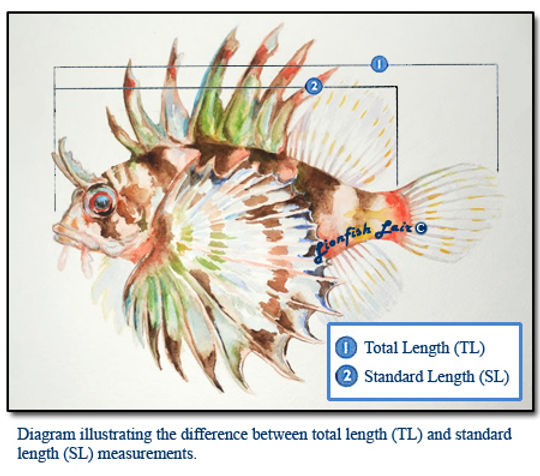

Maximum Size: 6”-8” TL (~ 15 - 20 cm).

Natural Habitat:Occurs in association with reefs, drop-offs, and rocky caves. Indo-West Pacific: Red Sea and East Africa to Samoa, north to southern Japan and the Ogasawara Islands, south to Australia and Lord Howe Island.

Depth: 3 - 80 m (~ 10 - 26 ft).

Minimum Tank Size: 40 g (~ 151 l).

The zebra is one of the two most common dwarf lions in the hobby along with the fuzzy dwarf, and one of the three most common lions in general, the third species being the large-bodied Pterois volitans. D. zebra can be identified by a dark spot on the lower portion of the operculum, the presence of two white spots (sometimes more of a free-form white hourglass) on the caudal peduncle, and dark concentric bands at the base of its beautiful webbed pectoral fins. The pectoral fin membranes extend almost to the fin ray tips, forming a non-incised web. Like most lionfish, the body pattern consists of alternating dark brown/reddish and light brown/off-white stripes.

In the wild, this little lion is fond of sheltered areas with lower current flow, so be sure to provide it with some sheltered areas in which to rest and avoid fast laminar flow. In the wild, D. zebrapreys mainly on crabs and shrimp, although they will occasionally eat small fish, and like all lionfish, is a crepuscular hunter.

Unlike D. brachypterus and D. barberi, this species is not sexually dimorphic, although very subtle differences between the sexes have been reported, such as larger heads and bodies in male specimens. It is also reported that just prior to spawning, the female zebra takes on a brilliant white color with a dark midsection. Since it is virtually impossible to sex this species, and males will fight, it’s best to keep a single specimen of D. zebra per tank.

In general, captive care for this fish is similar to that of the fuzzy dwarf.